Outerwear Fabric, Features & Construction Guide

Why Techwear?

Newcomers to the world of action sports often find the huge selection and wide range of outerwear prices bewildering. If you’re used to simply throwing on a denim jacket or windbreaker to head out on the town, it’s hard to fathom why on earth you’d ever want to buy a coat that costs as much as a used car, and yet experienced riders who seemingly don’t have money to spare routinely throw down for these garments, and for good reason.

Mountain climates in winter are unforgiving, and the challenge of protecting yourself from the elements becomes even greater when you’re participating in an active sport. Not only does your clothing have to keep precipitation in the form of snow and rain from penetrating, it needs to allow water vapor from perspiration to exit. That’s where waterproof, breathable clothing – we call it “techwear” – comes in. Unlike your jean jacket, which is fairly breathable but has no water repellency, or your raincoat, which might be pretty waterproof if it’s coated on the inside with Polyurethane but has little breathability – your ski or snowboard jacket and pants should do both well.

Waterproof, breathable fabric technology is a wild and rapidly evolving frontier with big dollars at stake. The dominant player in this game is the W.L. Gore Corporation, makers of GORE-TEX fabrics and a host of other products ranging from artificial blood vessels to guitar strings. Other large companies, like Japan’s Toray (Entrant® and Dermizax™), Polartec® (NeoShell®), Sympatex™ and General Electric (eVent™) are heavily involved as well, and many outerwear manufacturers have developed their own proprietary waterproof breathable fabrics (or licensed membrane technology from others); some examples are Helly Hansen (Helly Tech®), The North Face (FutureLight™), and Mountain Hardwear (Dry.Q™ Elite).

Construction Types: 2 Layer, 2.5 Layer, 3 Layer

These days, almost all fabrics used in ski and snowboard techwear are functionally very waterproof, and rely on a memrane of PU (Polyurethane), PE (Polyethylene) or PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) under the face fabric (the part you see) to keep water out and still let water vapor escape. As of this writing, PTFE membranes are being phased out because of environmental concerns, even by GORE-TEX (who built the category). Depending on where you ride, any fabric with a waterproof rating in excess of 10,000 mm (see our guide for an explanation) will likely keep you reasonably dry and comfortable even in a nasty storm. The differences in breathability, however, are dramatic. Why is breathability so important?

Realistically, if you’re an occasional rider who only skis or snowboards on lifts and never hikes or climbs in your clothing, a high breathability rating may not be that big of a deal. You’ll probably seldom work up much of a sweat and might find your dollars better spent on other gear or simply a few more days on the hill. If you’re a serious rider looking for lines that require hiking in the sidecountry or skinning all day long on backcountry excursions, you’ll want a garment that not only provides bomber weather protection but also packs small and allows you to work hard without trapping sweat next to your body. Good breathability doesn’t come cheap, but serious riders who realize its value are willing to pay to play and are often found wrapped in fabrics like GORE-TEX, eVent™, or Polartec® NeoShell®. It could be the difference between an epic day and a horrible one.

Waterproof breathable fabrics are typically classed as either:

2 Layer

2L construction is the most commonly used construction for outerwear. 2 Layer fabrics often use similar face fabrics and membranes as 3L, but there is no bonded third layer on the inside. Instead, there is a mesh or fabric lining that hangs loosely within the jacket. 2 Layer garments can potentially offer the same level of weather protection, but since there’s essentially another garment inside the shell, they’re considerably bulkier. 2 Layer models are usually quite a bit cheaper than 3L and 2.5L shells. If weight and packability aren’t an issue for you, this may be the best way to go.

2.5 Layer

2.5 Layer fabrics have neither the bonded mesh lining nor a separate sewn-in lining, but include a very fine raised pattern screened onto the membrane to keep it off your skin. The raised pattern helps to protect the laminate from your body oils, sunscreen, bug spray, and anything else that can break down the material over time. This is most commonly found in rain shells (see examples), but can be used for snowsports as well. GORE-TEX PacLite is probably the best-known example of a 2.5L fabric, and lacking a lining, is extremely light and packable. 2.5L jackets are commonly used as "emergency" shelter for backpacking, ski touring, and cycling when packability is critical.

3 Layer

A 3 layer fabric consists of an outer layer or “face fabric”, which is usually made of nylon or polyester and a “membrane” that’s bonded to it. Membranes are the waterproof layer and are most commonly made of Polyurethane (PU), expanded Polyethylene (ePE), or expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). Then, a very lightweight backing fabric is attached to the interior. It doesn't hang loose like a 2L, and helps to improve comfort by absorbing moisture and helping transport it through the membrane and to the surface of the face fabric. The interior lining also helps protect the waterproof laminate from being damaged by skin-borne substances like salt and oil. 3 Layer construction is the most advanced, protective, packable, durable and breathable construction method, as well as the most expensive. These pants and jackets excel in the most sustained extreme conditions, making them ideal for the action sports enthusiasts that need superior protection in a lightweight and durable package.

Fabric Thickness & Durability

The thickness of waterproof, breathable face fabrics varies enormously. Fabric thickness is measured as a function of thread weight, or “denier.” Denier is defined as the mass in grams of 9,000 meters of the thread used to weave the fabric, and common weights for outerwear shell fabrics range from around 30 denier (30D) to around 150 denier. An average "resort" jacket is usually around 70 to 80 denier. “Ballistic” weight fabrics used for high abrasion areas like pant cuffs (as well as packs and luggage) range somewhere between 300 and 1,200 denier.

“70D 100% polyester twill” means a 70 denier polyester fabric with a diagonal woven twill pattern is used. “N80p GORE-TEX Pro” stands for a nylon 80 denier plain weave face fabric with a GORE-TEX Pro membrane. A jacket made of a good 3 layer waterproof breathable fabric in a 40 denier weight will usually weigh less than a pound, and pack down to the size of a grapefruit, which can be a big advantage when the space in your pack is limited. A thicker 80 denier fabric will increase the weight and bulk of a garment, but provide much better resistance to abrasion and cuts. Manufacturers will sometimes include the actual fabric weight as well, which is expressed in grams per square meter (g/m²) or ounces per square yard (oz/yd²).

A Note on Waterproof Breathable Ratings:

Waterproof ratings are expressed in millimeters and indicate the height of a column of water that can be suspended over the fabric without leaking. Breathability ratings are expressed in grams, and indicate the amount of water vapor that can escape from inside a square meter of the fabric in 24 hours. A typical high end fabric may be rated at 28,000 mm / 20,000 g, while a mid-level fabric may be listed as 15,000 mm / 10,000 g. A few fabrics are rated in PSI (Pounds per Square Inch) – you can convert PSI to mm using the formula 1 PSI = 704 mm. For more information on waterproof breathable ratings, check out our Waterproof Ratings and Breathability Guide.

Fabric and outerwear manufacturers are often reticent to reveal waterproof breathable numbers, and to be fair, the testing protocols for these specs are very inconsistent. Many of the charts available on the web are misleading or simply not accurate, so beware – a good way of researching the merits of a particular fabric is to ask someone you trust who’s used it over a period of time in the climate you frequent. For our recommendations on outerwear by region, check out our How to Buy Outerwear for Skiing and Snowboarding by Region Guide.

Seam Taping and Sewing vs Welding

Tech garments are made up of separate pieces of fabric that are normally sewn together using needle and thread. The alternative to sewing is welding, which attaches the pieces using either heat-activated adhesive film or fuses the material using the heat generated by ultrasound. Welded seams have the advantage of being lighter and less bulky, as well as creating no holes for water to enter. Sewn seams have an advantage in strength, but must be sealed with seam tape to ensure they remain waterproof. There are many varieties of seam tape, with the best and thinnest requiring special machinery and very skilled operators (usually the cream of the factory’s crop). It’s common in the outdoor industry to use both methods in the production of a garment – sewn and seam sealed for stress-bearing areas around the arms or legs, for instance, and welded for pockets, zippers and adjustment cord hems.

On evo product pages, “fully taped” means that every seam in the garment is sealed, while “critically taped” means that only the most exposed seams are sealed – usually the neck, shoulders and front zipper for jackets and side and center seams for pants.

When it comes to sewing, some manufacturers do a better job of it than others. Arc’teryx, for instance, prides itself on maintaining a standard of 14-16 stitches per linear inch in its outerwear construction, where the industry standard is 8-10 stitches per inch. More stitches per inch means construction is slower and uses more thread, but the end result is a stronger garment with longer lasting seams.

Quality of the thread used is also a factor. The thread in your sewing machine at home – probably cotton-covered polyester in a #50 weight – won’t hold up well to the UV rays and abrasion your ski or snowboard clothes have to withstand. Most quality outerwear is sewn using a 100% polyester thread in a heavier #40 weight.

Built-in Insulation vs Shell and Midlayers

Ski and snowboard jackets and pants come in both insulated and non-insulated models. Insulation can take the form of either synthetic (usually spun polyester) or natural (duck or goose down) materials, and can be added to the lining of your garment. A common way to insulate a jacket is to “body map” it – using a heavier and warmer layer of insulation around the core (body) and a somewhat lighter version of the same insulation in the arms and/or hood. Synthetic insulation weights are expressed in grams per square meter of the fabric, so 100 gram insulation will be warmer and thicker than 60 gram insulation. A typical insulated winter jacket might say “80 grams body / 60 grams arms and hood”.

Note that an insulated waterproof breathable garment is always 2 Layer, as a lining between you and the insulation is needed anyway and it makes no sense to bond a lining above the insulating layer.

Down is rated on a “fill power” scale, with insulated garments normally using down in the 500-800 fill range. Higher numbers mean greater insulating efficiency and a higher price tag.

If the conditions you ride in are consistent, and you can pinpoint the level of insulation you are comfortable in, an insulated garment might be perfect. Likewise, if you run cold and would rather err on the side of warmth, insulation could make you happier. The downside (haha) of insulated garments is that you’re stuck with that level of warmth, even if the weather changes or you become more active.

The “shell and mid-layers” approach is more versatile, allowing you to pair a heavier or lighter insulating layer with a waterproof breathable shell. It can also end up being more expensive, but the ability to change the type of midlayer (or wear none at all) depending on the weather and your activity level might let you wear the same shell more of the time.

Some manufacturers offer garments with removable insulation which makes for a more versatile garment ("3-in-1" systems), but the attachment systems (usually zippers) add a hassle factor and bulk.

Generally, riders who stick to lift-served skiing or snowboarding during the winter months in a cold climate may do best with insulated outerwear. Those who ride in variable climates where temperatures go both above and below the freezing point, and those who like to search for fresh lines under their own power should probably think in terms of a shell/midlayer combination.

For more information on insulated garments and layering, check out our How to Choose Insulated Garments Guide and our How to Choose Base Layers and Long Underwear Guide.

Hardshell vs Softshell

When we speak of techwear, most people think in terms of “hardshell” garments. Hardshell jackets and pants are functionally waterproof clothes with a tightly woven outer fabric and little or no stretch. Past versions of hardshell fabrics had a reputation as “noisy” – they created a rustling sound when the fabric moved over itself, like when your arms rubbed over the body of your jacket. Hardshells also had a reputation for limited breathability, causing manufacturers to develop venting systems like pit zips (zippers under your arms that could be opened for venting purposes). Recent hardshell fabrics have improved markedly in both the noise and breathability departments, so if your waterproof breathable garment is more than a few years old you might consider an upgrade. Many modern hardshells incorporate some stretch, too, blurring the lines between the two categories.

Softshell garments are just that – the surface of the fabric has a soft “hand” and feels much like the knit fabric your mom or dad’s pantsuit was made of in the 80’s. Softshells are extremely comfortable, since they stretch when you move and have superior breathability. They’ve also come a long way in the waterproof category, and if kept clean and treated properly and regularly with DWR (Durable Water Repellent) can be a viable outerwear solution for many people.

The best choice for you depends. If you live and ride in colder, Continental conditions, where precipitation generally falls as dry snow, you may well be comfortable riding in softshell all season long. If you live and ride in a Maritime climate where fresh snow is often near the melting point, a softshell garment probably won’t cut it much of the time, and you should probably choose hardshell garments for their superior weather protection.

If you’re a backcountry fanatic who spends days out of the ski area proper travelling under your own power, a combination could be the best solution. A very light hardshell jacket combined with water-resistant softshell pants often offers the best compromise between emergency weather protection and breathable comfort.

A Note on DWR:

Almost all waterproof breathable garments are chemically treated with "Durable Water Repellent" (DWR) which allows water to roll off the face fabric before it even soaks through to the membrane - this is your first line of defense against getting wet. Originally, DWR molecules contained 8 carbon atoms (referred to as "C8") and later versions were "C6." Both were extremely waterproof but somewhat toxic and didn't break down once released into the environment. DWR formulas have changed dramatically over the years, with most now being "C0 (Zero)", and older DWR solutions containing PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances) were banned beginning January 1, 2025. New garments sold after that time should be PFAS-free (many manufacturers phased them out earlier).

Follow your outerwear manufacturer's instructions on how to best maintain waterproofness and breathability. Washing your outerwear, rinsing it twice and placing it in the drier on medium heat in order to "reactivate" the DWR is the most typical method of maintaining waterproofness. You shouldn't need to re-apply DWR often, so long as you keep your techwear clean!

Features on Top of Features

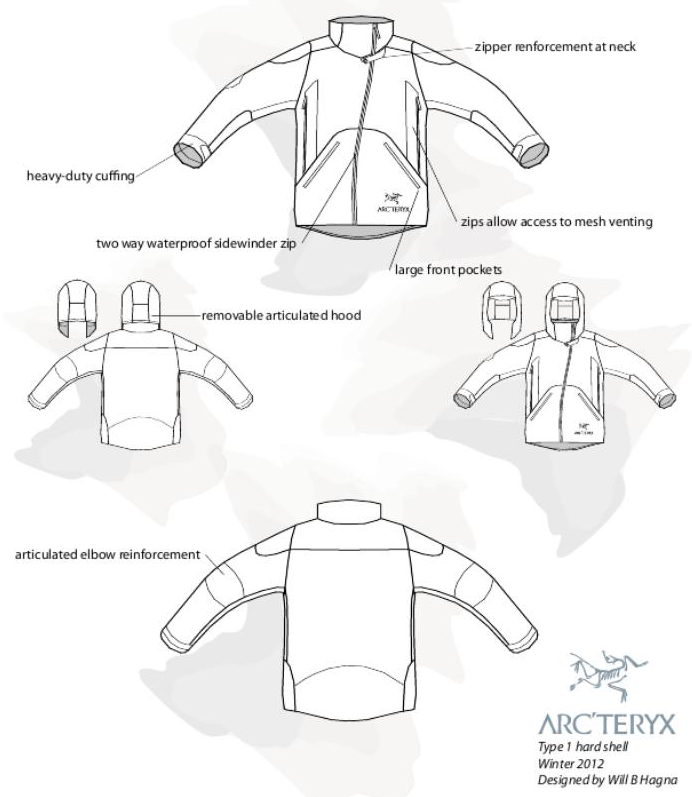

Sometimes it seems like the outerwear industry is in a race to see who can come out with the most features in their garments. Removable adjustable hoods, powder skirts, goggle pockets with built in wiping cloths, audio/media pockets, wrist gaiters, jacket/pant locking features, season pass holders, pit zips, zip out liners, you name it. How many of these things do you actually need?

It depends. If you like to listen to music when you ride, that dedicated phone pocket with cord routing is going to come in handy – you have to put your player or phone somewhere. If you ride in and fall in powder, a functional powder skirt will definitely help keep the snow out of your base layers. The same goes for pass holders, pit zips, goggle pockets and the like – if you use them, they can be quite nice.

So why is it that the garments at the very top end of the price spectrum usually have few of these features built in, and instead concentrate on high waterproof breathability numbers and lightweight packability? The market for high-end techwear is dominated by frequent riders who know what they want. Number one is protection from the weather, and the difference between a 10,000 mm coat and a 28,000 mm coat can be a deal breaker when you’re spending the entire day out in a 34F° (that’s 1° C for those not in the US) snowstorm. If you seldom fall, that powder skirt is just more fabric to deal with, and if you spend most of your days on the mountain listening to the soft croon of Mother Nature, you won’t need a music player, either. Recent advances in fabric technology have taken breathability to the point where you may not need pit zips. Dedicated skiers and snowboarders sometimes spend much of their time accessing out of-the way lines by booting or skinning, and often leave their shell in their pack while they’re climbing, so low bulk is more important than extra pockets. Think carefully about how you intend to use the garment and look to riders you admire to see what sort of clothing they prefer. Be realistic about the conditions you’ll likely encounter and how active you’ll be while wearing the garment and chances are good you’ll end up with something you love. Almost all outerwear you find these days is a huge step forward from what was available even a few years ago, so have fun shopping and enjoy being warm and dry on the slopes this season.

Learn More With Our Other Outerwear & Layering Guides:

What to Wear Skiing & Snowboarding

How to Choose a Ski & Snowboard Jacket

How to Choose Ski & Snowboard Pants

Jacket Fit & Length Guide

How to Choose Outerwear by Region

How to Dress for Backcountry Skiing & Snowboarding

Waterproof Ratings & Breathability Guide

Outerwear Construction, Fabric & Features

How to Choose Base Layers & Long Underwear

How to Choose Insulated Clothing

GORE-TEX® Fabric - How it Works & Product Testing

This is evo. We are a ski, snowboard, wake, skate, bike, surf, camp, and clothing online retailer with physical stores in Seattle, Portland, Denver, Salt Lake City, Whistler, and Snoqualmie Pass. Our goal is to provide you with great information to make both your purchase and upkeep easy.

evo also likes to travel to remote places across the globe in search of world-class powder turns, epic waves, or legendary mountain biking locations through evoTrip Adventure Travel Trips. Or, if you prefer to travel on your own, check out our ski & snowboard resort travel guides and mountain bike trail guides.

Still have questions? Please call our customer care team at 1.866.386.1590 during Customer Care Hours. They can help you find the right setup to fit your needs.